Jacob Hiatt Passes Prelims, Focusing on DNA as a Nutrient

When Jacob Hiatt first came to the David Lab as a rotational student, he was tasked with investigating what happens to plant and animal DNA from our diets as it travels through the human digestive tract. He used FoodSeq, a cutting-edge metabarcoding process developed by the lab, to analyze human stool and identify foods based on their DNA signatures.

In May, a year after officially joining the lab, Jacob presented his initial findings as well as an outline of his research aims to his PhD advisory committee, successfully passing his preliminary exams and officially moving into the dissertation phase of the program.

“This research has opened up this really interesting line of dialogue,” he recalls. “With my prelim, I was trying to home in on these questions around how DNA is digested by the gut, and then how is it being utilized either by the commensal microbes of the gut or by the actual host? Is it taken up into these organisms? And then, in what ways is it being integrated?”

Early data revealed that nearly all food DNA is degraded during digestion; understanding the mechanism through which this DNA is broken down and absorbed by the host could offer tools to create new metabolites, including new DNA, our core energy compounds ATP and GTP, or signaling molecules that control functions ranging from metabolism to gene transcription to selective permeability in cells.

Compared to lipids and proteins, characterizing DNA as a dietary metabolite is a relatively new approach. In the limited time this mechanism has been examined, it’s been through a pathogenic lens, addressing concerns around genetically modified organisms. By contrast, Jacob is studying the digestion of DNA from a nutritional perspective.

“There's a renewed interest in dietary DNA. We're eating less DNA in our diets; there's less DNA in ultra-processed foods, and we're eating more ultra-processed foods. We don't know what the health consequences are,” Jacob says. “People are starting to recognize that we don’t have strong tools to evaluate this.” PCR, the main tool used to characterize DNA, wasn't developed until the mid-1980s—decades after the foundational literature for similar mechanisms that detect lipids and proteins had been established. By then, the research focus had shifted, with the scientific community leveraging PCR and newer sequencing tools to explore different questions unrelated to dietary DNA.

“It’s kind of shocking how little we actually know about this,” he says. This deficit of research introduced a new challenge, namely choosing a specific area amid a sea of potential options. “I was trying to tackle too many things at too broad of a level, so I really focused on asking these more pointed questions.”

Jacob zeroed in on three specific aims for his preliminary, with the first two related to digestion kinetics. Aim 1 asks what host factors affect how DNA is digested and how those factors may impact the persistence of DNA from diet. The second brings microbiology into the equation. “I was reading through the literature, and there’s a good case that microbes are able to utilize DNA as a nutrition source,” he explains. This suggests that gut microbes are themselves digesting the food DNA, either for themselves or as part of a symbiotic relationship with the host. The final aim follows labeled DNA in mouse hosts to determine how specific metabolites are integrated into the body and where the ingested DNA ultimately ends up.

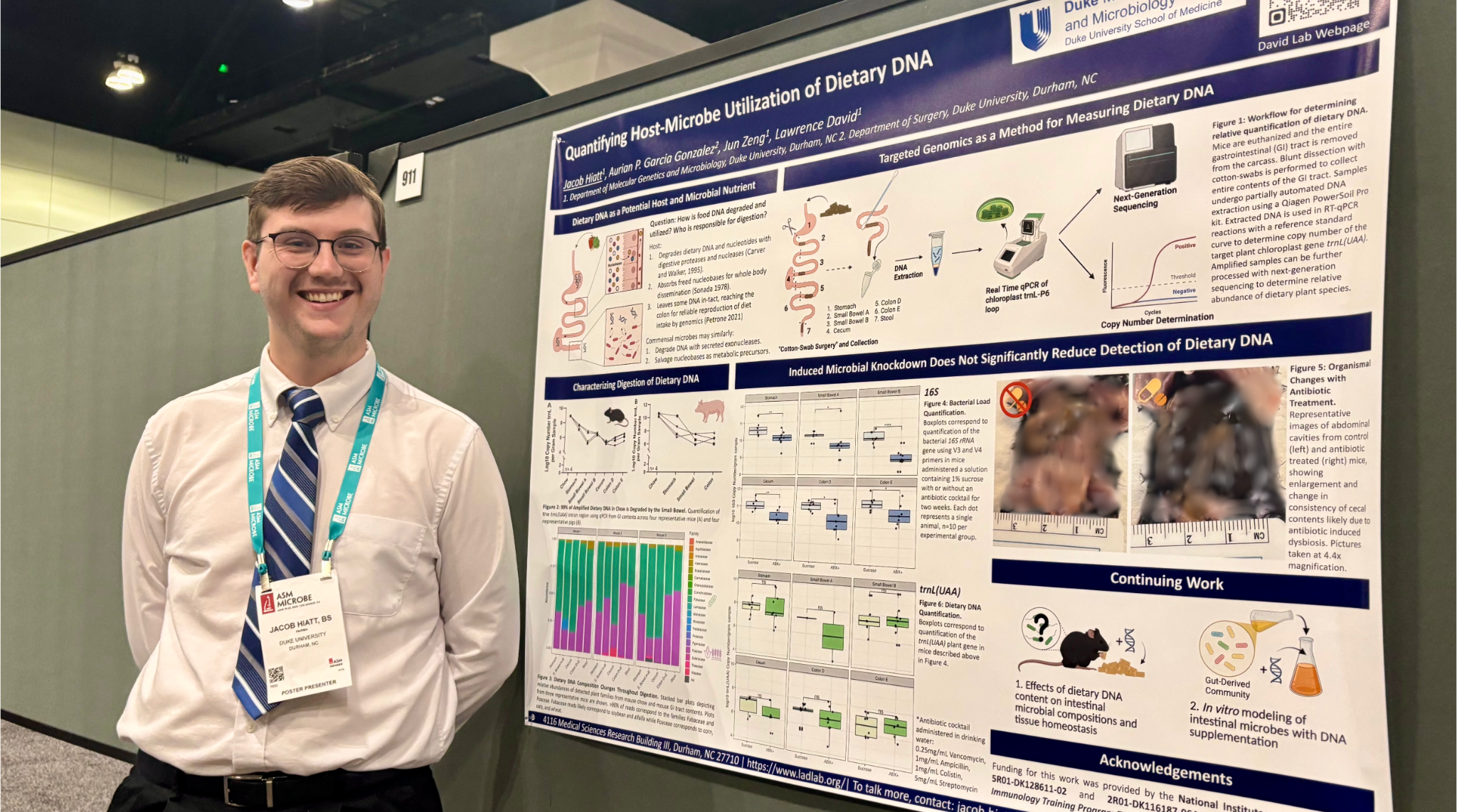

Jacob and Auri taking a fun break during the ASM Microbe conference in June.

Each of these aims uses mouse models, with Auri P. García González, a surgical resident and postdoc in the David Lab, providing invaluable guidance and mentorship. “I want to acknowledge Auri. She’s been incredible in everything she has done to help me formulate this project,” Jacob says. “We’re the two people in the lab asking these more physiological questions, so she’s able to teach me a lot of things. I think it kind of formed into this natural mentoring relationship and I'm very appreciative of that.”

Others in the lab have also shared their expertise and experiences to assist Jacob in crafting his aims and moving the research forward. For example, Jun Zeng, a fifth-year PhD student who studies diet-microbiome interactions in cancer patients, played an important role in helping Jacob develop his own core methodology. “The advisory committee also gave really great feedback during the actual preliminary exam,” he says. “Everyone's been very instrumental in getting me to this point.”

A month after passing his preliminary exams, Jacob attended the ASM Microbe 2025 conference in Los Angeles, where he participated in a poster session, presenting his research to participants and networking with potential collaborators. “The people I spoke with were surprisingly enthusiastic about these new lines of questioning, especially on the microbial front,” Jacob recalls. “I think there’s continued interest from many about how specific components of our diet impact health, which reaffirms the purpose behind my project.”

As Jacob begins his third year and dives deeper into the role of dietary DNA in human health, he’s eager to continue uncovering new findings using FoodSeq and novel approaches to a long-overlooked area of inquiry. “Specifically, I’m planning to assess whether supplementation and deprivation of DNA from diets impacts host physiology and health, which are projects I am very excited to see the answers from!”